Hiring a live-in domestic worker in Southeast Asia is not uncommon among middle and upper income families. These domestic workers are often migrants from other countries. Unfortunately, domestic workers – and especially those living with families – can face abuses such as no weekly day off, having to be on call 24 hours a day, not being allowed to keep their passports and not being paid a fair salary.

To address exploitation in the domestic work sector, IOM X created a regional video programme called Open Doors: An IOM X Production.

Open Doors aims to reach as many employers in the region as possible, in order to increase awareness of the exploitation of domestic workers and encourage employers to adopt better behaviours towards them.

Testing the impact of a regional programme requires a regional approach. Open Doors was tested with viewers in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand by IOM X’s research partner, Rapid Asia. In each of the countries, the video was shown to a sample of the intended target audience – people between the ages of 15-50. Most of the survey participants employed domestic workers (47% of Thai, 62% of Indonesian and 100% of Malaysian respondents), some of which were migrants and some of which were nationals of the country where they work.

Over 700 people were surveyed before and after watching Open Doors, to see what impact the programme had on viewers’ levels of knowledge, attitudes and intended practices towards domestic workers and their rights.

Surveyed viewers from Malaysia and Indonesia appear to have learned the most about domestic worker entitlements after watching Open Doors, as their knowledge levels increased by an average of 32 per cent. Thai viewers’ knowledge also increased, although to a lesser extent, at 17 per cent.

In all three countries, knowledge of a weekly day off and paid rest days was high, about 85 per cent of those surveyed knew about these rights. However, across the board, audiences from all three countries showed low awareness on what constitute fair working hours. This shows that there needs to be more efforts to inform employers that domestic workers deserve fair working hours, just like employees in any other sector.

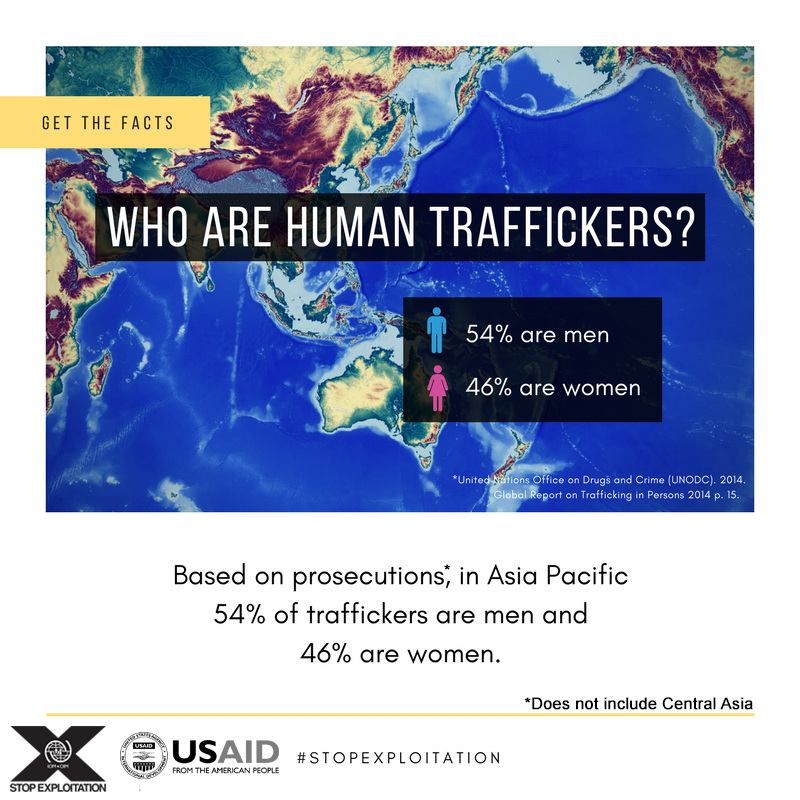

Unfortunately, negative attitudes towards migrant domestic workers were still expressed by an average of 42 per cent of the people surveyed after watching Open Doors. Shifting attitudes is generally an extremely difficult task that is unlikely to be accomplished after seeing one video. However, despite the high levels of negative attitudes, Open Doors was able to make a small dent. When comparing the scores of all three countries, ignorance, measured by asking participants if they agree or disagree with the statement ‘live-in domestic workers should be available to work at any time’, on average decreased the most (by 18%) in all three countries. The most remarkable shift in attitudes was found in Malaysia, where negative attitudes decreased by 19 per cent. Such a high decrease in negative attitudes speaks for the effectiveness of Open Doors to connect to employers.

The three-country survey found that intended behaviours towards domestic workers were high; although in general behavioural intent was high in the pre-survey already (at an average of 72%), it increased in all three countries, especially in Indonesia (up 16%). The most significant increase in behaviour was concerning the practice of advising friends who are about to hire a domestic worker. On average this behaviour increased by 18 per cent.

One interesting finding was that those who employ migrant domestic workers always showed higher levels of knowledge, attitudes and intended practices than those who employ local domestic workers. It was also found that those who were previously exposed to news around domestic workers had higher levels of knowledge, attitudes and intended behaviour, compared to those who didn’t. This shows that experience and exposure to information, and interaction with domestic workers, may contribute to a better understanding about domestic worker rights.

With about 84 per cent of surveyed viewers saying they found Open Doors interesting and learned something new, it can be said that across the region the programme accomplished its objective. The programme set out to raise awareness of the exploitation that domestic workers face, and to encourage employers to adopt positive behaviours that will reduce exploitation. Encouraged by these positive findings, IOM X continues to disseminate Open Doors across the region.

To read the full comparative impact assessment study of Open Doors in Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand click here.